“Called to Arms”

“In the summer of 1861 they left the rolling farmland of Wake County. Many of the crops were still in the fields, the animals needed tending, cows required milking, firewood needed to be chopped for the upcoming winter, and fences needed mending. Most were young, strong men; their muscles hardened by countless hours swinging axes and plowing fields. They left behind frame farmhouses with river-rock fireplaces, corn-shuck mattresses and Sunday dinner tables laden with cured hams, collard greens, and sweet potatoes, cut corn, biscuits and rhubarb pie. Behind them lay the familiarities of boyhood: a favorite fishing hole, a one-room schoolhouse, a deep woods hunting trail, corn cribs, haylofts, berry patches, a tail-wagging coon dog and pew-filled sanctuaries that rang with hymns and preaching on Sunday mornings. Left behind too in the outburst of Southern patriotism and pride were fretful mothers, solemn-faced fathers, teary-eyed sweethearts and among the older recruits, anxious wives and children-all hoping the men would win the war quickly and soon return home.”

— As quoted from Covered with Glory written by Rod Gragg.

Each recruit once called a small farm his home, where he toiled from dawn until dusk. There were few aristocrats among them; the great majority owned neither slaves nor large plantations. Gragg says, “They were men who earned their living with honest sweat, and owed not any man. They were seasoned outdoorsmen who were comfortable with firearms and who were trained from childhood to shoot with deadly precision.” Their average age was 23 years old, with the oldest being 55 and the youngest, a tender 15. Gragg goes on to say, “Most were reluctant secessionists. Their ancestors had

battled the British on famous fields

such as Kings Mountain and Guilford

Court House and like most North Carolinians, they had been slow to give up on the Union. Although wary of secession, they refused to join the North in making war upon their Southern brothers.”

On May 1, 1861, the North Carolina legislature voted that counties should elect delegates who would determine whether North Carolina would remain in the Union. The delegates, convening in Raleigh, voted unanimously that the state would no longer be a part of the United States of America. The Ordinance of Secession states: “We do further declare and ordain, That the union now subsisting between the State of North Carolina and the other States under the title of the United States of America, is hereby dissolved, and that the State of North Carolina is in the full possession and exercise of all those rights of sovereignty which belong and appertain to a free and independent State.”

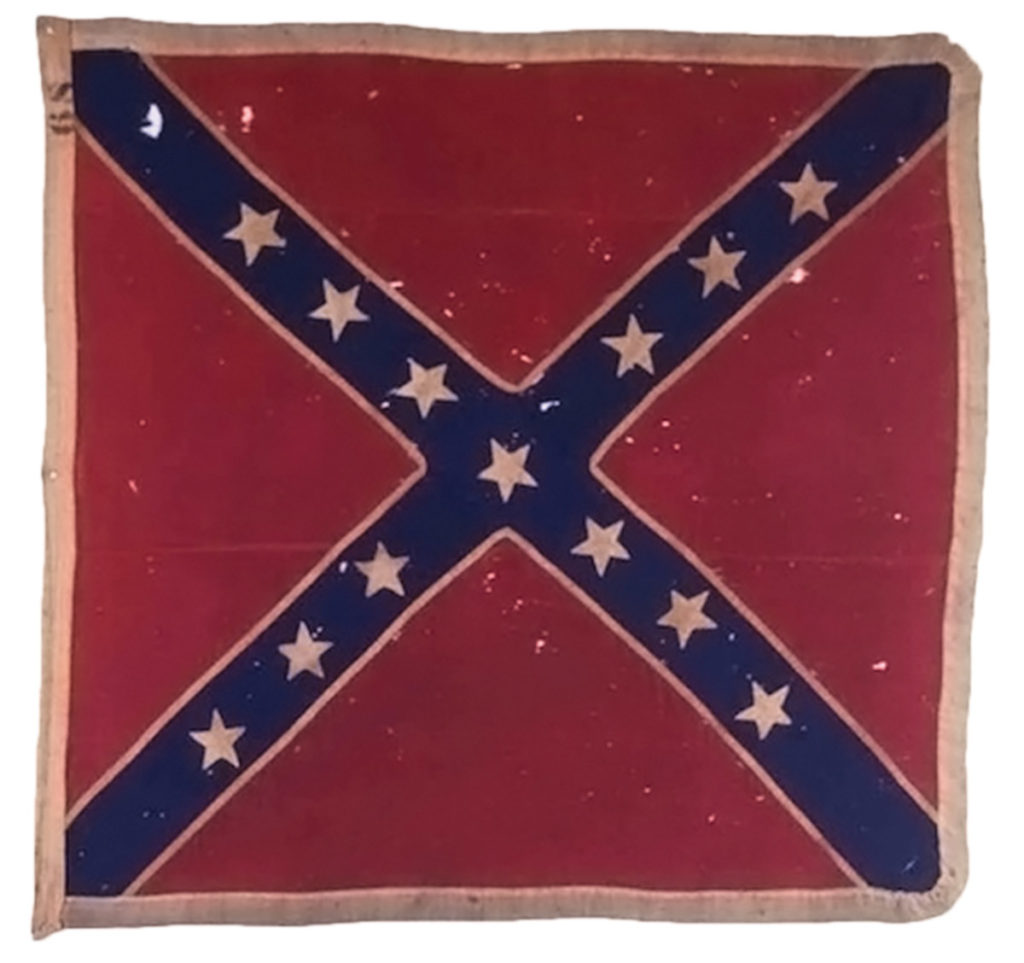

North Carolina was the last Southern state to join the Confederacy. The factors and events that led the state to secede from the Union included social structure, intra-state sectionalism, and industrial organization, in addition to the influence of national debates over slavery and states’ rights.

In the long and bloody conflict that followed, North Carolina lost more troops than any other Confederate state. Among those troops were several units of men from the Holly Springs area that answered the “call to arms” by the newly formed Confederacy. The men that left with Captain Oscar Rand that summer made up the 26th Regiment Company D, or “Wake Guard”. The company made itsway to Raleigh and reported to the camp of instruction at Camp Carolina, also known as Camp Crabtree. For the new recruits, life at Camp Carolina proved to be a radical change from their civilian lives. Like many Civil War soldiers, their enlistment in the army meant they were away from home for the first time.

This regiment would forever have its name etched in the annals of history as holding the distinct honor of reaching the Confederate “high water” mark during the Pickett-Pettigrew Charge as well as the tragic distinction of suffering the highest casualties of any unit, Confederate or Union, during the Battle of Gettysburg.

Among the ranks of Company D, 26th NC Regiment were James Theopholus Adams who had enlisted at age 21 and was appointed to second lieutenant the same day. Adams rose in the ranks to lieutenant colonel and was in command of the unit at the Battle of Gettysburg.

Upon his homecoming, he quickly immersed himself in community work, served numerous years as the Masonic Lodge #115 master starting in 1867, and was instrumental in reestablishing the schools that had been closed for so many years.

Britton Suggs Utley opened a medical practice and a drugstore upon his return. Utley was appointed postmaster in February 1880, served as the Masonic Lodge #115 master for many years and assisted in the rebirth of the Holly Springs Academy as the Holly Springs Institute in 1883.

James G.M. Adams and David C. Adams rebuilt family farms and helped boost the economy of the war-ravaged area.

Another Wake County regiment was the 3rd North Carolina Cavalry (41st NCT) COMPANY I, known as the “Wake Rangers”. Among those ranks were George Benton Alford, who would return from war and see the potential of Holly Springs and set actions in motion to make it happen. Alford would get Holly Springs incorporated, bring multiple businesses here, and get the railroad to locate here, grow rice in a local pond, and run a turpentine distillery and lumber mill. In addition, he would help reestablish the schools, serve as the postmaster and justice of the peace, and establish a newspaper. His payroll records show his employment of a large percentage of the men in town. William Washington Clements, son of Woodson Clements, who had one of the first stores in the area. Clements would carry on with his father’s mercantile store upon his return from war. William M. Jones, who helped his father, Wesley Thomas Jones, with a large mill on a pond known today as “Thomas Mill” carried on with that family business boosting the market with jobs.

These war weary soldiers had returned to an almost deserted ghost town. Their homes and businesses either had been pillaged or destroyed by retreating Union troops, a very bleak picture to behold for these men. Their once thriving farms laid fallow and overgrown. The resolution and tenacity of these men with their united purpose was to build their hometown to the prosperous, thriving community that they envisioned. The determination to create a better quality of life for their children and for future generations is evident in the works and accomplishments of these returning war veterans.

Once again, fields would yield sweet potatoes and corn. Churches would be filled with families singing hymns. As a community, they would show the resolve that only could be described as doggedness. These returning soldiers built the foundation of Holly Springs for future generations to expand and improve upon and set into motion the prosperity that we enjoy today.